The commercial version of this is on my main blog.

This was one of my worst mistakes: I took a job I didn’t like for the prestige. And maybe two of them: I told them I needed a lot more money instead of just quitting.

Act 1: Spring in Paradise

Things were really (perhaps even the true Californian “wrily wrily”) good. The story begins in Spring of 1981 with ultimate happiness, which is – Samuel Johnson said this – happiness laced with the anticipation of more happiness. I was finishing my MBA at Stanford. I loved my classes. My wife loved simple town-house living in student family housing on campus. The kids went to great public schools without having to cross a street. The rent was cheaper than our fifth-floor apartment in Mexico City by half. Although I couldn’t afford the MBA without working virtually full time, the work was good, mostly at home, and the money was enough. I consulted with Creative Strategies.

And things were going to get even better. Job prospects at graduation were fabulous. High-paying jobs with lots of perks and lots of, well, awkward to say it, but, power. Recruiters came from far and wide. Good job offers were everywhere. So I had a lot of choices. I was a 33-year-old Stanford MBA, American fluent in Spanish, former Business Week correspondent in Mexico, etc.

Act 2: Like an Idiot…

And I, like an idiot, took a job I ended up hating: McKinsey Management Consulting in Mexico City. It paid great, there were perks, and, crowning my mistake, I think I was way too influenced by what looked good to my peers.

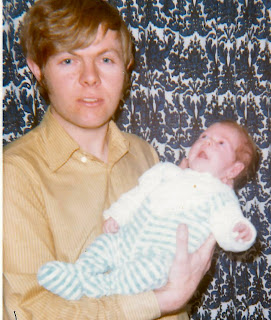

I should have known better. The job I accepted was meant for a very ambitious 25-year-old single person with no family and no relationships, ready to work long hours for six years to win the partnership. I, on the other hand, was a 33-year-old married father of three, with (we learned a few weeks later) Cristin coming.

And, worse still, I was already “tainted” by 10 years of entrepreneurship. I made more money freelance than on salary. I paid my own way through Stanford Business School and supported my family while I did.

Things went badly, of course. Details accumulated. At six or so when there was no work to do I went home to my family, instead of waiting until the partners left three hours later. I did that repeatedly, despite warnings that it wasn’t to be done. I objected when one of the partners left his sixth car in my parking space. I disagreed with a partner about peso futures. I objected to a mandatory company meeting over a five-day weekend at a beach resort with no family allowed.

So of course I had to quit. That’s obvious. But here’s how I made it worse. There is a lesson here.

I didn’t tell the managing partner I was quitting because I didn’t like him, his other partners, McKinsey Management Consulting, or Mexico City. I didn’t tell him I made a mistake. I didn’t want to look that stupid.

Here’s where the lesson really smarts. So instead of saying something like the truth – speaking of looking stupid – I said I was sure the peso was going to be devalued so they needed to pay me a lot more money.

And the next day they offered me a lot more money.

And the day after that I quit anyhow. Talk about dumb! How bad did I look when they gave me the raise and I still quit.

Act 3: Thrilling Conclusion

There is a useful point here. I’ve brought this up before. Don’t hide the truth with what you think might make you look good because it can end up backfiring, making you look bad. Don’t guess what the other party won’t accept and ask for that when what you really want is something entirely different. They might give you that, and then you look like an idiot.

We’d borrowed about $3,000 to buy a fancy-but-nauseous (some of you might remember) Volskwagen camper conversion. And (like an idiot, again) I decided to pay them back my signing bonus.

I returned to Creative Strategies. They were nice about it, they seemed very happy to get me back. I called my parents, asked them to pick us up at SFO with two cars. We travelled back from Mexico with Laura’s teddy and 12 checked bags. We stayed with my parents in Los Altos for more than a month while some of you went to Loyola School and we purchased the house we quickly hated at 530 Suisse Drive.